Interview 003: David Siev

David Siev is a filmmaker based in New York City. His documentary feature film, Bad Axe, chronicles the life of his family in 2020, as they tried to keep their restaurant afloat through COVID and navigate the volatile political moment as a family of color in their rural, predominantly white town. It won the Critics' Choice Award for Best First Documentary Feature earlier this year, and it was also one of the 15 documentaries shortlisted for Best Documentary Feature Film at this year’s Oscars.

Let's start all the way back at the beginning: I’m curious to hear when and where you grew up and what it was like for you to be multiracial Asian in this context.

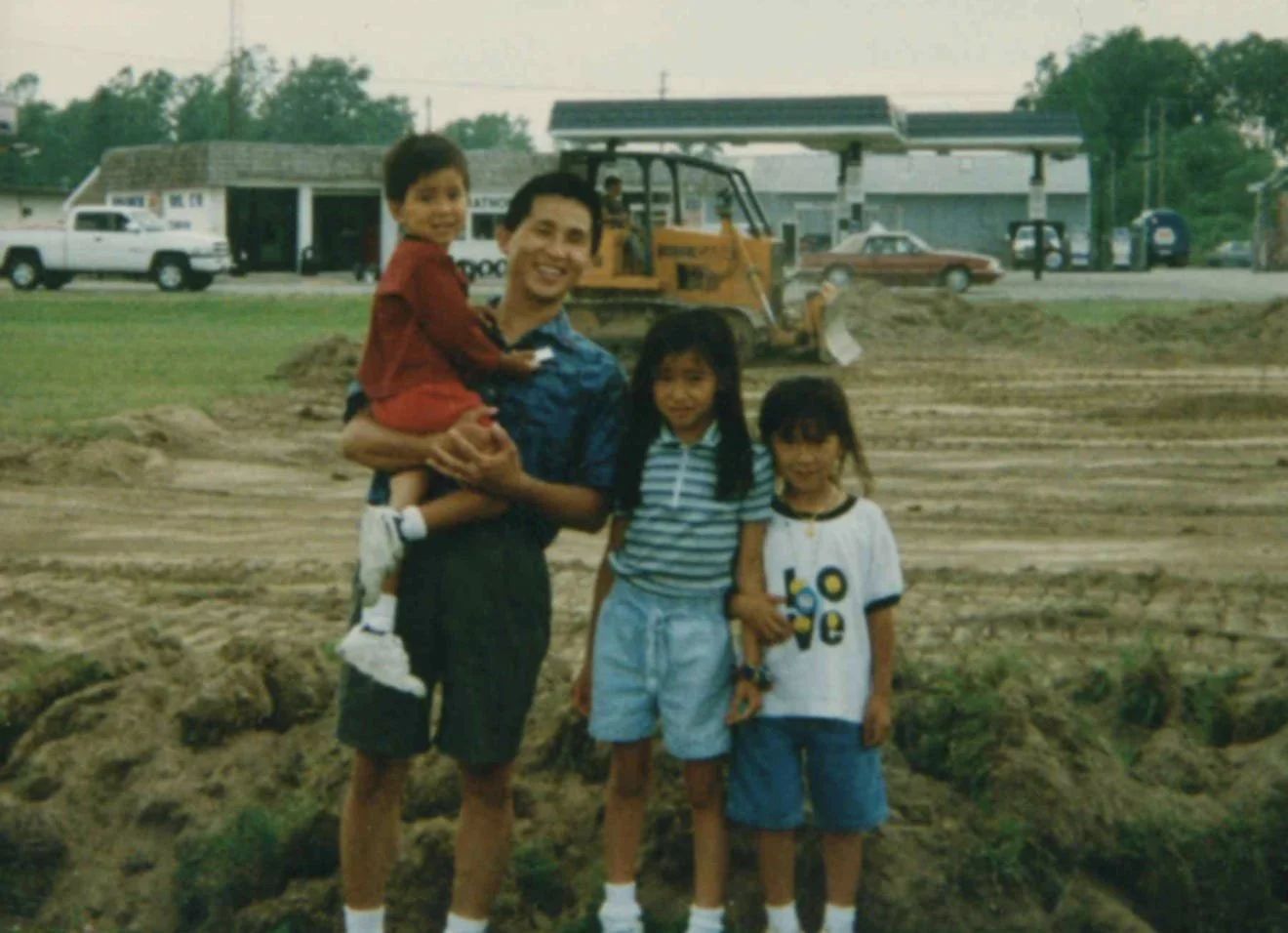

I grew up in this small rural farming community called Bad Axe, Michigan. Bad Axe is a beautiful place to grow up – it's the type of community where literally everyone knows everyone. I graduated with maybe 85 kids, the same kids I went from K through 12 with. So it has that sense of community, given how small the population is. I think it's less than 3000 people. My parents moved there from metro Detroit in 1998. I was five years old at the time, and they built and opened a donut shop. It was always a dream of both of my parents to own their own business, and the move to Bad Axe was their first step in doing that.

Ninety-seven percent of Bad Axe’s population is white, and obviously my family falls in the 3% of multicultural families. My mom is Mexican American and my dad is Cambodian. He was a Cambodian refugee that came to this country in 1979 after surviving the Killing Fields, so it's interesting that of all places, these two individuals decided to stake their roots in this town called Bad Axe, where they begin building this restaurant, this donut shop, the American dream.

My experience of growing up in Bad Axe is familiar to a lot of multicultural kids living in areas that are primarily white – we always wanted to fit in. We didn't want people to think of us as being different or other. The reality is you can't hide that because it's who you are. But growing up in Bad Axe, I wanted to just fit in with all my white classmates.

In terms of examples of how you hide your identity – for me, it was something as small as being conscious of what foods I would bring to lunch. There's this dish I still love – growing up, it was a comfort lunch food I wouldn't need anyone to cook for me. It's just white rice and dry shredded pork. We call it ba-yang in Khmer. You see it at the Asian grocery markets.

I served it to my kid yesterday for breakfast.

What do you call it?

In Mandarin, it's rò sōng. The rò means meat and the sōng means loose, I think?

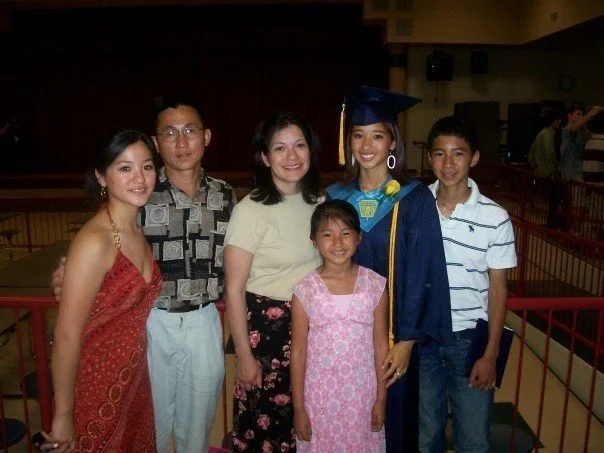

Rò sōng, okay. I remember packing it for lunch one day in kindergarten or first grade, and kids thought it was so weird and made fun of it. As a kid, you're embarrassed because you're like, “Oh wait, why is this the food I'm eating while the rest of my friends are eating brown paper bag lunches with peanut butter and jelly sandwiches?” And I stopped bringing it because I felt embarrassed that people thought it was so weird. That's just one example of this assimilation, this way we tried to hide a part of our identity. I think I speak even for my sisters – I have three sisters, two older ones and one younger one – and we all have our own journeys, our own experiences of hiding that identity. For me, it wasn't until I went to college – I went to the University of Michigan – that I was exposed to a completely different community. I started meeting other Asians, other Mexicans, Latinos, and you realize that this experience you think is so specific to you, it's actually a shared experience among people from these backgrounds living in communities like Bad Axe. That's when I began this journey, this one I'm still on, of trying to find out who I am. What does it mean to be a first-generation Cambodian-Mexican kid? What is it that makes me me? That was something I didn’t want to think about growing up. But as we get older, we want to discover what makes us who we are.

I relate so much to all of that – growing up as one of very few kids of color in my community and just wanting desperately to be white. I have similar stories about asking my mom to stop packing me Chinese food for lunch and asking for the sandwich and the Capri Sun. Going to Michigan was also a big turning point for me because I was exposed to this rainbow of people I had never been exposed to before – so many different kinds of Asians, specifically. I had no idea there was so much diversity within our community in terms of backgrounds and personalities and interests. It blew my whole world open.

And now you live in New York, so it feels like you've gone from one end of the spectrum in terms of diversity to the other.

It’s the complete opposite. I live in Astoria specifically, which is a neighborhood in Queens, and I believe it's one of the most diverse neighborhoods in the entire world. It’s such a contrast to Bad Axe.

How does it feel to move around in Astoria as opposed to moving around in Bad Axe?

I love to write in coffee shops in Astoria. Sometimes when you take your headphones out, you hear people speaking all sorts of languages from all different parts of the world, all in one coffee shop, and it's like, “Whoa, this is like a microcosm of America.” It's so interesting seeing that because as a kid in Bad Axe, I would’ve never thought this existed.

I find myself constantly gravitating towards Bad Axe. My wife and I spend so much time traveling – we're either here in Astoria or in California where her family lives or in Michigan. There’s a lot I still appreciate about Bad Axe – it's such a beautiful community. I wouldn't have chosen to be raised anywhere else. I truly mean that. Growing up in Bad Axe shaped my family's bond, who we all are, who I am. And it makes me appreciate this experience of being a filmmaker and living in New York – both of them make me appreciate each other. I'm grateful I get to have the best of both worlds because Bad Axe has this real sense of community that’s harder to find in Astoria or New York. New York is so big. It doesn't feel like home in the same way Bad Axe does.

It's so interesting how you put that – living in Astoria, you've gained this incredibly diverse landscape, but you’ve also lost that sense of rootedness in a community where everybody knows you. So even though Bad Axe is lacking in diversity, what you have there is this sense of being known as one of the 85 kids in your class and part of the family that runs Rachel's Food and Spirits. It’s nice that you get to move back and forth between these worlds and get different needs met in different places.

You talked about starting college as being a formative moment for you in terms of thinking about yourself as a person of color. Are there other events you can think of that were formative in terms of how you thought about yourself as a multiracial person?

Quite a few. The first time I had the realization that I was different was at a very young age – it was my first time riding the bus to school and I remember this kid telling me I couldn't sit with him. He called me the N-word and he's like, “You can go sit somewhere else, but I don't sit with N-words.” And my feelings were totally hurt. I was super-embarrassed and I had no idea what that word meant. When I came home from school that day, my mom explained to me that word had to do with skin color. I think that was the first time I felt the sense of other, as a five-year-old kid. It's crazy how something like that can stick with you from such a young age.

Another instance like that happened when I was a teenager. I remember this Little League game in a town outside of Bad Axe called Cass City, 20 minutes away. I was starting the game as a pitcher. As I was warming up, before the first batter came on deck, all the kids in the dugout started squinting their eyes at me. It really got under my skin, because I was old enough to understand what that meant. And it really rattled me. Now that I reflect back on that as an adult, I'm like, “How did the coach or any of the other parents or players allow that to happen?” I don't know if my coaches were aware of that moment at all, but it really stuck with me. And that's the thing about assimilating – we could try to do it for so long, but we’re often harshly reminded we’re different. And that was one moment I clearly remember.

Fast-forwarding to college – like I said, this was my first time meeting other individuals like me. It took a long time to get to this point where I’m proud of being Mexican, of being Cambodian. Because that's something I always tried to hide growing up.

There was one other Chinese American kid I went to school with. He reached out to me a few weeks ago to congratulate me on Bad Axe. I feel this sense of guilt because I felt like me and him should have been better friends growing up. But I think I would often – consciously, subconsciously, whatever – avoid him because I didn't want people to see us hanging out and be like, “Oh, those are the two Asian kids.” You know what I mean? His parents also owned a restaurant in Bad Axe. We were friends in private, because he took Taekwondo class with my dad and we would celebrate Chinese New Year together. But in public, we didn't really hang out. We were friendly with each other, but we were certainly much friendlier in private when it was just the two of us in these safer spaces. I wish I could go back in time and change that. I think a lot of kids, or at least people with experiences like me, wish we could go back in time and say, “Why did I try so hard to assimilate? Why did I try so hard to fit in?” But that’s part of the experience of growing up.

That's so relatable. I think that's so common for people of color who grow up in predominantly white environments. Because exactly as you said – we could have been allies with that one other Asian kid in our class, and that probably would have been good for everyone. But we were so desperate to fit in and not be seen as that, so strategically, it made more sense for us to distance ourselves from that person. Which is terrible in hindsight, but in the moment, it feels like survival.

I was also thinking, when you were talking earlier about the heartbreaking incident on the baseball diamond: No matter how hard you try to assimilate, eventually your face gives you away. Assimilation is a losing game.

It’s a losing game. And it's interesting how our parents think of assimilation – my parents have never really admitted to it. They always had this attitude of “We never tried to hide who we were, but we came to this town and we kept our heads down. We didn't say too much and we just worked hard and became part of the community.” And I'm like, that is assimilation.

It's passive assimilation.

It's passive. And for me and my siblings, it was more of a direct approach to assimilation.

Active assimilation.

Yeah, active assimilation. Whereas with them, it’s passive assimilation. And you see that come to light in Bad Axe.

That’s one of the things I appreciated about Bad Axe – there’s the prevailing narrative of what an American experience is, and then there's thousands of other American stories that don't get told. But the more representation we have of those stories, like Bad Axe, the less people like our parents will feel the need to passively assimilate and the less kids like us will feel the need to actively assimilate. And that's a beautiful thing.

It really is. And that's why representation in film and TV and media is so crucial, because we need to see our different experiences reflected on the screen. I can't tell you how many screenings I've done where young kids from the AAPI community and multicultural families were saying, “Wow, your experience was my experience. So grateful that you shared your family's story.” And I say to them, “I hope it inspires you to share yours.” We need to open up this conversation about what the American experience is. It's not just one thing – it's many different experiences. America is built on the experiences of immigrants and the experiences of my families, of this Cambodian refugee and this Mexican American woman coming to Bad Axe to start their American dream. I can't think of an experience more American than that.

Truly. I'm curious – we've touched on how you identify, but when you have the complete freedom to identify however you want, how do you identify racially, and has this changed over the course of your life?

It's changed quite a bit. Growing up, I identified as Chinese American – not even Mexican, to be honest. Maybe it was easier to say I was Chinese American, which is technically right – my grandparents are from Cambodia, but their grandparents came from China, so I have Chinese blood in me. But it wasn't until college, when this interest in being a storyteller and sharing my family's story began, that I started asking my dad about these stories of Cambodia and I began to shift the way I identified from Chinese to Cambodian. And the Mexican side is something I still struggle with – not in terms of calling myself a Mexican, but in terms of like, “What is that part of my identity?” My mom's parents never taught her Spanish because they wanted her to learn English. And they passed away when I was younger, before I went through this identity crisis, and I never got to learn much about their stories or where they came from. It wasn't like my dad's side of the family, where my dad has always been so open about sharing these stories with me and my uncles and aunts have too. I didn't get that from my Mexican side. I'm very proud to call myself Cambodian and I'm proud to call myself Mexican too, but I don't feel connected to it in the same way. So this is a journey that keeps on going because I want to understand this other half of my identity, and I don't know how to do it yet. I feel like storytelling will probably be the avenue for how I explore that. I'm 29 years old and have a lot to learn, obviously, about life and the world, but also about myself as well.

That makes so much sense. I wonder too, having seen the documentary: Your father experienced Cambodia firsthand. He's got such clear memories, clear stories. You grew up with your Cambodian grandmother. You don't have to go that far back to reach the Cambodian roots. Those stories feel more present in a way that maybe the Mexican ones don't because your grandparents immigrated, not your parent, and they passed away and it's harder to glean those pieces of culture.

It's so much harder. The Cambodian stories do feel so present. My dad has always shared stories with me of the Cambodian Killing Fields and everything he went through. That's why I identify as Cambodian, because I’m proud to call myself a son of a refugee.

A survivor.

A survivor, right? His story is part of my story and it feels very present, whereas this other side of me, this Mexican side, is more distant than I would like it to be. And I'm half Mexican – it’s half of my identity. Hopefully we can talk in a few years and I’ll have a better understanding of this. Identity is an evolving process that we go through.

For sure. I don't know if you’re interested in having children, but if you choose to, I feel like that really begs these questions of “How do I want to transmit culture to them? Being Asian American or Cambodian or Mexican – how do I want that to look for them?”

Absolutely. My wife and I talk about it – she's 100% Puerto Rican, so our kids are going to be 75% Latino and 25% Cambodian. So how we’ll present culture to them is something we think about, and I think it’s part of what's driving me to learn about this other part of who I am.

That makes a lot of sense. I'm curious if being multiracial has impacted how you understand or experience other identities you have, like sexual orientation or nationality or sex – if there are any intersections that being multiracial has influenced or added another layer to.

In a sense, absolutely. It's allowed me to have empathy for other people who are struggling with their own identity, whether that’s being LGBTQ or feeling other because they're different from what society thinks is normal.

We’ve been able to show the film to audience members from other communities and see how they've related to ours. We did a screening in Los Angeles, and one person in the audience was from Bad Axe. He came up to me afterwards and gave me a big hug and was completely in tears. He said, “Even though your experience is different, I grew up gay in Bad Axe and I never knew how to fit in or where my place was. Seeing you share your family story and it being so hopeful and seeing the conversations that it started, it's been healing as far as how I view that community.” So in that sense, being multiracial makes me want to stand in solidarity with other communities, with people who are trying to be exactly who they are.

I love that. Changing gears: How has being multiracial has been a challenge for you in your personal or professional life?

Representation in the industry I work in is a challenge. When we were trying to find people to finance Bad Axe, everybody passed on it. Once the film was complete, we tried to sell the film to all the major streamers – Hulu, Apple, everyone. The feedback that we got across the board was, “We love it, but we don't think there's an audience for this.” That was heartbreaking and frustrating. We couldn't even find a sales agent – they're the liaison between the filmmakers and the streamers and the studios – until the last minute.

We ended up premiering at South by Southwest on a Monday at 12pm. I didn't know if anyone would show up, and it ended up being a packed theater. And once the lights came on and the credits rolled, it was met with so much love. We received a standing ovation and I cried like a baby, seeing this theater full of strangers in tears and connecting with my family's story. It was validation that our story does matter. People are going to connect with it. We ended up selling the film a week later to IFC Films. But that anxiety and frustration with the industry was very real. And you're seeing other films get financed and bought, and you scratch your head, like, “Why do these stories matter more than my family's?”

We’ve taken Bad Axe to over 30 festivals for the past year, and it was incredible to be on this ride because people were connecting with our story. By the time the Critics’ Choice and the Oscars shortlist came around, it was like, “Oh, you guys are wrong. These stories are important. My family's story is important, and there is an audience that cares about hearing these stories.” We're just not seeing enough of them get made. So while representation has come a long way in the past ten years, there's still a much longer road ahead. We're seeing films like Everything Everywhere All At Once, we're seeing Michelle Yeoh and Ke Huy Quan. It's incredible, but that doesn't mean we've done enough. If you look at the five Oscar nominees for best documentary feature, only one of them is from a filmmaker of color, and that's not enough. I'm hopeful for the future ahead for AAPI and multicultural filmmakers – people do care about our stories and they're going to listen, but we need to change the structure of our industry and who the gatekeepers are, who decides what films get made. I mean that at many levels – it’s with critics, studio heads, directors, writers, sales agents. We didn’t meet a single sales agent of color because there's not that many of them. There needs to be a huge structural change in the film industry. And it comes down to representation.

How has being multiracial been an asset to you in your personal or professional life?

This might sound super-cliché, but it’s made me proud of who I am – proud of the background and the history I come from. I’m this brown Cambodian-Mexican kid from the Midwest and I wouldn't trade that for anything. I want to continue sharing my stories and my family's stories and I want to continue uplifting other people like me. I want to continue contributing to this dialogue of what the American experience is. I’m proud to be part of this movement – it gives me something to wake up and look forward to doing every day. That's how I feel like it's enriched my life, through that motivation, but also through the people I've met. Look at me and you speaking right now. It’s fantastic.

It is! As we wrap up our time together, what advice do you have for kids or teenagers or young adults who are growing up multiracial Asian?

This might sound simple, but I think it's important: Learn your story and then go and share it. That's what I wish I had done at an earlier age, but hindsight's always 20/20 and I'm doing that now. Learn who you are, learn what your story is, and when you're ready, go out there and share it, because I truly think representation through storytelling is how we change the world.

Bad Axe is available to stream on AMC+ and available to rent on YouTube, Apple, and Amazon.